In this blog we consider representation in innovation and inventorship, looking at diversity and inclusion (D&I) from an intellectual property (IP) perspective. We discuss whether the patent system is inherently biased towards specific genders, races or ethnicities and then re-frame this issue as a sustainability challenge. We also make suggestions to empower innovators and level the playing field.

Have we done enough? It’s a simple question but it prompts us to engage in the difficult task of constructive introspection. It is also perhaps the ultimate question for developed and civilized institutions when it comes to the topic of diversity and inclusion (D&I). These initiatives are undoubtably important to the sustainability agenda, but they can be vague and even unhelpful unless properly contextualised. This article considers the notion of D&I in intellectual property and the wider innovation ecosystem, sketching some possible recommendations for empowering innovators.

When it comes to the business of innovating, the patent has a special power because of the monopoly it confers on the owner. Patents are part of a wider system of knowledge governance, which have become useful proxies for innovation. It is assumed that successful inventing results in obtaining a patent.

Although anyone can apply for a patent, not everyone is entitled to grant; that usually belongs to the inventor, unless someone, like an employer, is given privilege. However, an inventor’s position is not guaranteed: the only automatic right they can enjoy is being named on the patent, particularly for those ‘paid to invent’[1].

In theory, such a system, which gives protection to ideas, should be accessible to all those that need to use it, regardless of gender, race and ethnicity.

But data reveals a different story.

It can tell us who is (and who is not) being recognized and ultimately rewarded for their contribution to the branches of human knowledge. Perhaps, more importantly, it encourages us to reflect on who never got a seat at the table.

Keep reading to learn more about representation in innovation and inventorship:

- The importance and legal significance of inventorship

- Why lack of representation is a systemic problem

- What’s in a name? Measuring diversity and inclusion in inventorship

- Diversity as a driver of sustainable innovation

- The ‘4 Rs’: Responsibility, rewards, recognition and remuneration

- Recommendations for empowering innovators

- Closing the gap: final remarks

Is patent law inclusive?

Patent law purports to be neutral. The law claims to look impartially at issues like novelty, inventiveness through the eyes of the person skilled in the art. But just as these have been difficult lines to draw, inventorship also does not exist in a vacuum.

History tells us of both cautionary tales and successes of minority inventors. Ada Lovelace, the mother of the computer. Mary Kenner, the Black woman who revolutionized the menstrual pad, filing five patents. And Alan Turing the pioneer of modern computer science, convicted and only now pardoned for being a gay man. These individuals, and the many others who are forgotten, overcame great adversity to deliver technologies that have vastly improved our daily lives.

Patent rights are exclusionary by design, held up by the principles of ownership and territoriality. So long as IP rights exist there will always be a separation between the IP-haves and have nots. That is how the system functions, but it cannot excuse everything.

In the early patent system, many occupations from which IP might be expected to arise were closed-off to sections of society. Cultural (mis)appropriation and exploitation have featured heavily. In the modern patent system, greater protections are being given to traditional creativity and cultural expressions e.g., handcrafts, folklore. This allows indigenous communities — those that are otherwise often excluded from the patent system — opportunities for protection[2].

However, the bigger picture is still problematic. Patent rights are exclusionary by design, held up by the principles of ownership and territoriality. So long as IP rights exist there will always be a separation between the IP-haves and have nots. That is how the system functions, but it cannot excuse everything.

Why lack of representation is a systemic problem

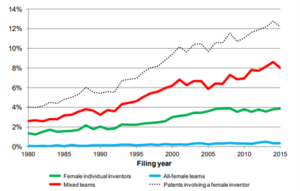

We know from research that today’s inventors are mostly male. The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) reported that only 16.5% of inventors named on international patent applications were women[3]. Estimates suggest that gender parity will not be reached until at least 2058 at the current pace. Similarly, research published by the UK IPO in 2015 suggested that women represented less than 8% of British patent applications[4]. The proportion of all-female teams was an even rarer occurrence making up 0.33% of inventions in 2015[5]. The USPTO has reported on their progress in 2020, with the number of patents with at least one female inventor increasing to 21.9%[6].

Teamworking: Female inventors on GB patent applications by inventor type 1980-2015

Source: UK IPO (2015), ‘Gender Profiles in UK Patenting: an analysis of female inventorship’

To speak solely in terms of a ‘gap’, is an oversight; we should also be thinking about the space, between academia and industry, where minorities might be lost. In the life sciences sector, women receive more than half of new PhDs but only make it on to 15% of patents.

It is more than just a numbers game too. In STEM occupations where men and women are equally distributed, research shows that women are less likely to engage with the patent system. Statistically, women are also likely to be named on patents alongside men rather than individually. Globally, women make-up about 35% of those in STEM education[7]. To speak solely in terms of a ‘gap’, is an oversight; we should also be thinking about the space where minorities might be lost, including between academia and industry. In the life sciences sector, women receive more than half of new PhDs but only make it onto 15% of patents[8].

These disparities extend to the prosecution and examination process. Research by Yale identified that women’s inventions had a significantly higher chance of being rejected. Their patents were 2.5% less likely to be appealed and of those that were granted, they included more words which reduced the scope of the claimed invention and thereby the monopoly[9]. Examiners were similarly found to disregard prior inventions because of the gender of their originator[10]. Only 28% of patent attorneys registered with the U.K. Chartered Institute of Patent Attorneys (CIPA) identify as female[11]. Yet, over half of respondents surveyed thought that the profession was inclusive[12]. The situation is similar with examiners as only 21% of UKIPO examiners are female, and 24% of EPO examiner posts are filled by women[13].

Inventorship is therefore socially constructed. It is replicating, and inadvertently embedding, power-structures and biases we see in the real-world.

What’s in a name? Measuring diversity and inclusion in inventorship

Patents contain bibliometric information such as the inventor’s name, country of origin and details of assignment. Disclosure of demographic information is usually not requested by patent offices or academic journals. Most approaches are therefore onomatological. They use the etymology, history, and statistical usage of names by indexing census data for example, to infer probable characteristics like gender, race and ethnicity.

This approach is problematic namely because of its binary nature (specifically when it comes to gender), reliance on self-reporting and statistical limitations.

Existing research is also patchy. Studies have overwhelmingly focused on gender. Race and ethnicity are scarcely talked about in the literature and there is next to no reporting on characteristics like sexual orientation or disability. This is compounded by insufficient country-level data and lack of frequent reporting. For this reason, data largely reflects a Western perspective.

Numerical approaches do not capture actual experiences and anecdotal accounts of prejudice and discrimination in patent-intensive fields (although there is no direct evidence of this). They therefore gloss-over factors like scale, complexity and intersectionality.

The methodology isn’t perfect, but it is at least measurable. Bibliometric approaches allow us to understand yesterday’s hierarchy and give us the springboard for tomorrow’s policies.

Diversity is a driver of sustainable innovation

Inventors are not the only ones harmed by underrepresentation. Non-inclusive processes have the potential to further embed the biases of their creators. The impact is likely to be substantial in a world where algorithmic approaches and automation have become the norm. We need to contemplate the wider social, economic, moral and even environmental consequences for society. The benefits of a diverse workforce are well-documented in research. The idea that ‘diverse teams deliver’ has become a maxim but it also reflects the importance of bringing unique perspectives, experiences, and cultures to the table. This also means acknowledging that equality in innovation is not just about equal opportunity for inventors but democratizing technology.

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) explicitly recognize D&I in:

- SDG 5: Gender equality

- SDG 8: Decent work and economic growth

- SDG 9: Inclusive and sustainable innovation

- SDG 10: Reduced inequalities

Specifically, SDG 9 incorporates inclusive and sustainable development infrastructure, together with innovation[14].

Therefore, sustainability cannot be achieved without inclusivity. If we accept that patents are critical to the success of the SDGs, then D&I in innovation ought to properly be framed as a sustainability challenge.

From an economic standpoint, studies have found that eliminating the shortfall of female holders of science and engineering degrees would increase GDP per capita by 2.7%[15]. Including more women and Black Americans in the initial stage of the process of innovation would increase GDP somewhere between 0.64% and 3.3% per capita.

The ‘4 Rs’: Responsibility, rewards, recognition and remuneration

While individual attitudes play a significant role in creating an inclusive innovation culture, institutions should be responsible for delivering ‘the 4 Rs’ — taking meaningful responsibility, providing adequate rewards, recognizing contributions and, where possible, remuneration.

Without adequate representation, it can be harder to solve real-world challenges that disproportionately affect minority groups. From this standpoint, facilitating meaningful access to the patent system could enable access to technology. This leads to a series of moral questions. Have the wrong people been unjustly recognized in the past? Are we recognising the right ones? Or are we simply overlooking technical contributions?

For an individual that identifies as a minority in an inventor team, for example, there may be many factors which influence the likelihood of patent recognition e.g., research and development processes, policy, gender and cultural differences. Getting or not getting a granted patent may amplify, affirm or entrench certain biases.

Incentivizing creative productivity goes to the heart of the patent system and this is part of the allure of working in STEM industries. So even if patents are not awarded equally, are they equally attractive to everyone?

Of course, the patent system was not necessarily designed with inclusivity in mind. However, it raises a fundamental question—can a system fixated with property ever be an equitable one? Or is it, as data suggests, inherently biased towards specific genders, races or ethnicities?

There are no easy answers nor is it productive to suggest that the system was broke to begin with.

In future, we might challenge some of the assumptions in law and policy, allowing regulation to play a more active role in fostering inclusivity. Until then, individuals and organizations should take collective responsibility to empower innovators.

Recommendations

Change needs to be implemented at the global, organizational and individual level. While there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach, this section provides suggestions for empowering innovators:

- Develop programs to increase diversity in STEM and patent-intensive fields. Incorporate training, inclusive policies and processes. Increase IP proficiency in higher education, alongside mentorship, networks and industry partnerships. Further understand the experiences of minorities interacting with the patent system.

- Conduct a ‘diversity audit’ where possible. Treat D&I as a sustainability challenge and where possible reporting of salary data could take account of patent ownership information, supplemented by survey feedback. Take meaningful action through ‘Diversity Pledges’, manifestos and quotas.

- Further research needs to be considered. For example, use bibliometric approaches to compare industries and D&I conversion from academia. Additionally, legal scholarship, socio-ethical (e.g. looking at dynamics in mixed inventor teams) and cross-cultural research may be beneficial.

- Continue efforts to analyse and collect demographic data within patent offices. Patent offices can assess the feasibility of voluntary disclosure of inventor profiles[16]. Closely monitor unconscious bias in the patent examination process. This could be supported by training and even legislative instruments.

- Partnerships, knowledge sharing and matrixed collaboration. Patent offices and companies could issue guidance to other country offices/participants, sharing knowledge, know-how and best practices. This could include an open-source API, repositories for D&I resources and studies comparing the effectiveness of initiatives in different jurisdictions.

Closing the gap: final remarks

Underrepresentation is not just a thing of the past. It exists all around us. The patent system is no exception; in fact, it is a poignant reminder. This blog has put forward evidence that exclusivity is not just feature of patent ownership, it is embedded throughout the entire IP lifecycle. It is true those ‘paid to invent’ will typically not become the owners of their inventions but this misses the point. Having opportunities to invent and, if successful, be named on a patent, is the moral right of an inventor. Lack of representation does not just hurt individuals, it can also have social, economic and ethical consequences particularly when it comes to achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals. The above recommendations provide a starting point for stakeholders looking to address these challenges generally, while acknowledging the role of the patent system as a tool to address inequality.

Stay up to date

At Clarivate™, sustainability is at the heart of everything we do, and this includes support of human rights, diversity and inclusion, and social justice. Read more about our commitment to driving sustainability worldwide and see highlights from our 2021 Clarivate Sustainability Report. You can also read more about the research and trends in each of the Sustainable Development Goals in our ongoing blog series.

References

[1] E.g. UK PA 1977, s 13

[2] WIPO (2007), ‘Intergovernmental committee on intellectual property and genetic resources, traditional knowledge and folklore’

[3] WIPO (2020), ‘Gender Equality, Diversity and Intellectual Property’ <https://www.wipo.int/women-and-ip/en/#:~:text=2020%20statistics%20reveal%20that%20only,only%20be%20reached%20in%202058.>

[4] UK IPO (2015), ‘Gender Profiles in UK Patenting: an analysis of female inventorship’ <https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/514320/Gender-profiles-in-UK-patenting-An-analysis-of-female-inventorship.pdf>

[5] UK IPO (2015)

[6] USPTO (2020), <https://www.uspto.gov/about-us/news-updates/uspto-releases-updated-study-participation-women-us-innovation-economy-0>

[7] Women in STEM Statistics (2022)

[8] Jensen et al. (2018), ‘Gender differences in obtaining and maintaining patent rights’

[9] Jensen et al. (2018), ‘Gender differences in obtaining and maintaining patent rights’

[10] Shen and Zingg (2020), ‘Patent Examiners and the Citation Bias in Innovation’

[11 Intellectual Property Owners Association (2022), ‘Diversity in the European Innovation Industry and IP Profession’

[12] IP Inclusive (2021), ‘Benchmarking Survey- IP Inclusive’

[13] Intellectual Property Owners Association (2022), ‘Diversity in the European Innovation Industry and IP Profession’

[14] This is further reinforced in Paragraph 2 of the Lima Declaration

[15] Hunt et al. (2012), ‘Why Don’t Women Patent’

[16] It is noted that this is resource-intensive and needs to adhere to data protection standards.